A personal tribute to John Archer

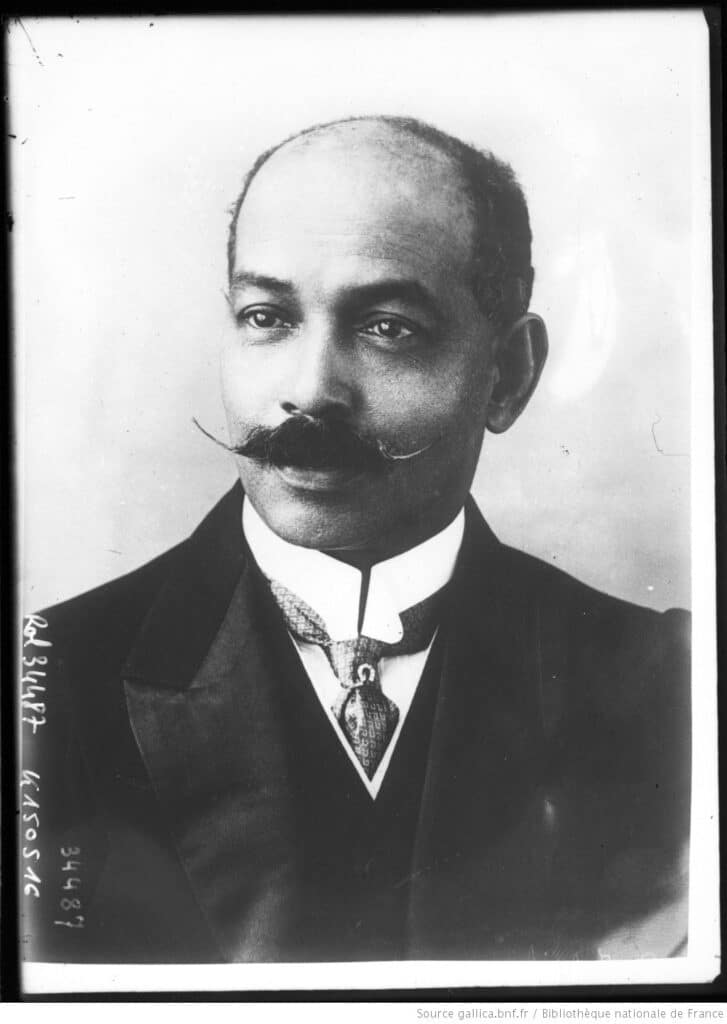

As part of Wandsworth Art’s Black History Month programme, which celebrates and honours work by local Black artists, writers, and community leaders and the great contributions they make to the rich culture of Wandsworth, Esuantsiwa Jane Goldsmith writes a personal tribute to John Archer (1863–1932), who was elected mayor of Battersea in 1913, making him London’s first Black mayor. Archer earned his living as a prizewinning photographer, and ran a photography studio in Battersea Park Road. A full biography of Archer’s life can be found on the British Libary’s website.

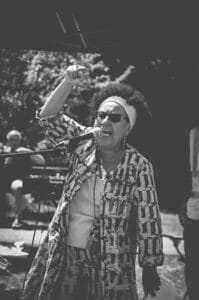

Esuantsiwa Jane Goldsmith (Esua) is a Black Mixed-Race writer, facilitator and activist of UK-Ghanaian heritage, living in Wandsworth. Her prizewinning memoir about mixed race identity, The Space Between Black and White, was published earlier this year. Read more about Esua’s work here.

Growing up in 1950s Britain as the Mixed-Race daughter of a single, White mother, I was an ‘only-one’. I spent my first weeks of life in an unmarried mothers’ home in Richmond, and my early childhood in my grandparents’ home on the Shaftesbury Park Estate, around the corner from Battersea Town Hall, now Battersea Arts Centre. I had no connection with my absent Ghanaian father, not even a photograph, and I got racist comments in the street and in the playground, with no one I could talk to. There were no books or stories that reflected my experience or the way I looked, which had a profound effect on my sense of self and identity.

In Brixton, just a few miles away from where I grew up, the Windrush generation had been putting down roots six years before I was born, but as a small child I rarely saw another black or brown face. Communities were tightly-knit; people worked, shopped, and socialised locally with family and neighbours. It was a very different world from the multicultural London we know today. I was loved, that’s for sure, but there is a difference between being loved and feeling you belong.

Imagine how I felt then when, in my late teens, I first heard about John Archer from my grandfather. “Did I ever tell you we used to have a Mayor in Battersea who was your colour?” Grandad asked me. “John Archer was his name, good bloke –West Indian father, Irish mother, one of the first black men to get elected in Britain. I used to see him at the socialist meetings up at the Town Hall, ‘eard him speak several times, when I was active in the Communist party.”

As a young woman with an emerging political consciousness and a hunger to work out my identity, here was the role model I was looking for. A man who looked like me, with a Black father and White mother, who had achieved great things and worked for all the things I believed in: equality, socialism, justice.

As a left-wing activist my grandad moved in John Archer’s world in the 1920s. Grandad was a self-educated Communist party member, a lifelong trade unionist, and skilled bricklayer at Morgan’s Crucible company. Grandad recalled that John Archer received a great deal of racial prejudice while he was campaigning – people said he wasn’t even British, and abused his Irish mother for marrying a Black man. But in his election speech as first Black Mayor in London in 1913, Archer proclaimed, “You have made history tonight. Battersea has done many things in the past, but the greatest thing it has done is to show that it has no racial prejudice, and that it recognises a man for the work he has done.”

I was impressed that despite having experienced such a lot of racism while campaigning, Archer still had the generosity of spirit to say that his election proved that there wasn’t any prejudice in Battersea. In the 1950s, two decades after John Archer’s death, I had still been called racist names on the streets of Battersea. It is strange how isolated I had felt in the very same neighbourhood. As the only brown kid on the block, with the most visible half of my personal story missing, I felt like an alien dropped from outer space. I wondered how John Archer had felt as a Mixed-Race man in a predominantly all-White society. Like many Mixed-Race people, his looks were racially ambiguous, and the press speculated that he could be Burmese, Hindu, or even Parsee. Being Mixed-Race means your identity is often called into question, and it takes courage to know who you are when you are frequently called upon to explain yourself to the world. Not so much ‘who are you?’, as ‘what are you?’

Travelling the world for my work I have also received some wild guesses about my identity – Philippina, Indian, Black American, even Chinese. Archer’s Mixed heritage may have helped him successfully navigate many different spaces, despite the challenges. He often proudly referred to himself as a ‘man of colour’, a Black man and ‘a race-man’. As a sailor, born in Liverpool, Archer had already travelled the world and had lived in the US and Canada before settling in Battersea with his Black Canadian wife, Bertha, demonstrating that we can equally be citizens of the world and citizens at home. We can ‘belong’ in many different places.

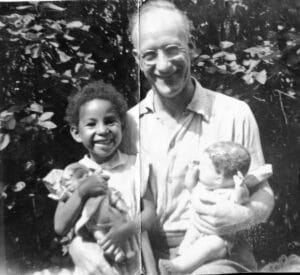

He knew his election as Mayor would give confidence to Black people around the world struggling for equality and independence. He had a Pan-African vision, becoming the first President of the African Progress Union, and chair of the Pan-African Congress in London. I can appreciate how important his African identity was to him. It was not until my mid-thirties that I finally traced my father in Ghana, and was delighted to discover that he was an activist and politician himself, and had also been a strong supporter of the Pan-African Movement in the 1950s in London when he met my mother as a student here. In 1957, he had joined Ghana’s government, the first country to achieve independence in Africa.

As a local politician Archer brought people together with his humour and his friendliness, despite the turbulent political climate. He actively supported other local leaders, acting as election agent for Shapurji Saklatvala, one of the first Indian MPs in Britain, and Charlotte Despard, a well-known suffragette. He was ahead of his time, a man of many parts – an effective campaigner for a minimum wage for council workers, women’s suffrage, anti-war and anti-vivisection. John Archer’s local community spirit shines through in many ways, as a champion of the poorest people and chair and Governor of local committees and institutions such as Battersea Polytechnic and Nine Elms swimming club. He even included education, swimming, professional singing, medical studies, and photography among his many interests and occupations. The range of his activities and pursuits is astonishing and must have taken enormous courage as one of the few Black Mixed-Race activists around. In my own career I have often found myself an ‘only-one’ or a ‘first’ on Boards and in organisations – the only brown face and often the only woman too – with all the responsibilities, expectations and ‘only-ness’ that entails.

John Archer was one of the few Mixed-Race public figures I heard about as a young woman, and his life undoubtedly inspired me and many others committed to social, racial and gender justice, weaving together those golden threads of internationalism and local activism that light up his story. His tremendous legacy is gradually being recognised. I’m looking forward to seeing his statue erected in Battersea, a memorial that will tell a very different story than the many statues around Britain commemorating slave-owners and colonial victories.

Today, as in John Archer’s day, we are again on the cusp of seismic world change. Covid-19 has exposed the racism, sexism, and inequality still existing in institutions and in the world system, especially affecting the most vulnerable and disadvantaged people. At the same time, it has shown us there’s another way. Communities have blossomed, awareness has heightened, Feminism and anti-racism are alive and vibrant as never before. These days I am active in the Wandsworth Black Lives Matter Movement, inspired by the huge upsurge in anti-racism around the world. John Archer’s life is the embodiment of acting local and thinking global, a continuing source of inspiration to new generations of activists worldwide.

Esuantsiwa Jane Goldsmith, October 2020

“Archer’s life undoubtedly inspired me and many others committed to social, racial and gender justice, weaving together those golden threads of internationalism and local activism that light up his story.”