When Matisse and Moore came to Battersea Park

Between 1948 and 1966 Battersea Park became a world-famous gallery under the open skies, hosting an innovative series of outdoor sculpture exhibitions that propelled modern art’s biggest names into the British public’s consciousness.

In the summer of 1948, during a buzzing cultural season that included the Olympics being hosted in London – the first games after a twelve-year hiatus during wartime – over 150,000 people headed to Battersea to see an ‘epoch-making’ exhibition. [1] It is said that people came from all over ‘the Empire and the World’ to take a turn around our local park and appreciate some of the world’s most innovative sculpture. [2]

In 1946, Patricia Strauss, a socialist journalist, art collector, and then vice-chair of the London County Council’s Parks Committee, first proposed the idea of an outdoor exhibition of sculpture in one of London’s central parks. She knew her wish to showcase the vanguard of modern sculpture to the masses might be a hard sell to her more traditional colleagues, yet she persisted nonetheless, writing:

Public interest in the arts is increasing but sculpture is rather the Cinderella – largely I think because people have so little opportunity to see it. Sculptors declare that their work… can only be properly viewed out of doors, but as far as I know there has never been an open-air exhibition of sculpture in this country… My idea is not merely to exhibit the work of Royal Academicians but also of Moore, Gordine, Epstein, etc., and thus show our public and the world the trends of modern sculpture. Indeed, I would like it to be truly an exhibition of Modern Sculpture; and if the discussion aroused is controversial, so much the better…[3]

As she’d predicted, her proposal was promptly dismissed by her staid colleagues as too radical, expensive, ‘a silly idea’. [4] However, in early 1947, Strauss was appointed Chair of the committee. By the end of the year hesitancies had been overcome and plans for an outdoor exhibition that would blend international modern and classical sculpture had been voted through.

*

In 1948 Britain was still very much gathering itself after the physical destruction and economic chaos of the war. With an optimism and brio that characterised the period, there was much noise in artistic circles that recovery would usher in an exciting era of socially-oriented culture, with art playing a key role in the effort to build back better and fairer. The new government had recently set up the Arts Council in 1945 to help develop the arts as a tool to educate and entertain not just the opera-going cultural elite but the whole of society. As the world’s first series of sculpture exhibitions in public parks, Strauss responded to these calls to revive the visual arts for everyone’s benefit.

Battersea Park was the perfect location – accessible to the factory workers of south London without being a million miles away from the bohemian and intellectual playgrounds north of the river. Furthermore, the park’s picturesque Winter Garden suited Strauss’s preference for ‘naturalistic landscape gardening’ over the formal landscapes of London’s royal parks. [5]

The deliberate informality of the outdoor surroundings looked to overcome the barriers, both literal and psychological, that typically surround artworks in museums. Here, most unusually, it was agreed that visitors would be able to wander around the sculptures, which were free from cordons, touching the forms as they so wished.

With the further aim of demystifying abstract sculpture for the general public, a programme of public lectures and a lantern slide promotion was shown in regional cinemas for thirteen weeks prior to the exhibition opening. Battersea libraries encouraged visitors to borrow art books, even publishing a pamphlet illustrated with a cartoon of a baffled spectator standing in front of a Moore-inspired sculpture in a park. Local retailers jumped on the marketing opportunity, using sculptures in their shop window displays to rouse the curiosity of shoppers and commuters.

Strauss was joined on the organising committee by Henry Moore, the leading British sculptor of the time, who acted as chief advisor on the siting of the sculptures throughout the park. A scale model of the park was made, upon which miniature sculptures were positioned and re-positioned until the exhibition design was decided. Barry Hart, Moore’s former tutor at the Royal College of Art, served as Exhibition Manager.

*

The struggling European art world, also struggling to build itself back up from the wartime rubble, sprung into action upon the exhibition’s announcement, with artists, dealers, museums and galleries all vying to have their sculptures included. Unsurprisingly, the logistics of staging the exhibition was something of a fraught nightmare. Resources and materials remained extremely limited after the war: the use of electricity to install the sculptures was such an issue that it required the Ministry of Fuel and Power’s authorisation; even building plinths was a headache as materials were prioritised for housing reconstruction.

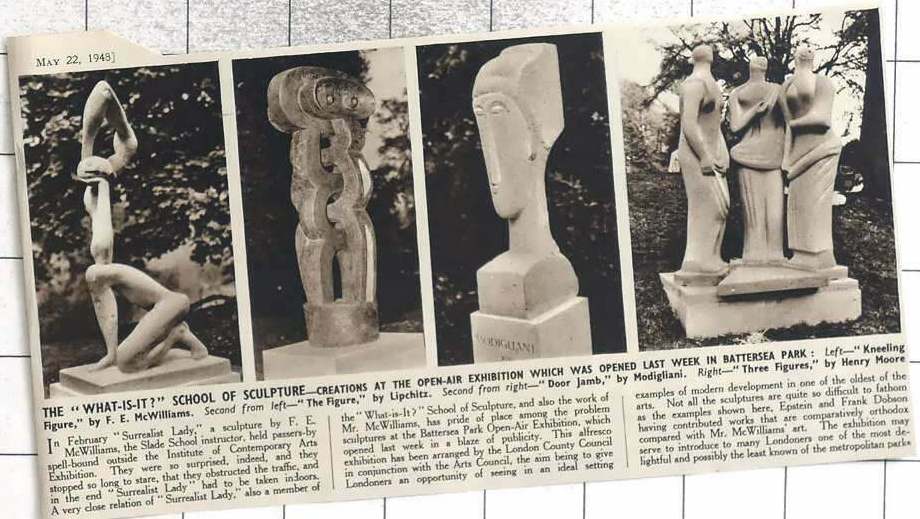

Nonetheless, the final result was the most comprehensive presentation of twentieth-century sculpture ever then seen in Britain. As Eric Newton wrote in the exhibition catalogue: ‘this exhibition is an experiment and an unusual one.’ [6] Among the selection of works were those by artists who had fled to England to evade Nazi persecution, such as Siegfried Charoux, Uli Nimptsch and Franta Belsky, all of whom were passionate that art be seen in public spaces, accessibly to ordinary people. 17 of the 43 works defied the conventions of a classical aesthetic, challenging the public’s understanding of what sculpture could be. ‘Master’ sculptors included Charles Despiau, Aristide Maillol, Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani, Auguste Rodin and Ossip Zadkine.

In his review, the artist Patrick Heron expressed his pleasure in viewing sculpture outside of the traditional confines of the museum:

It is lit, from below, by a hot yellow-green light off the lawns; and, from above by a cold blue from the sky. Then the white of direct sunlight and its corresponding dark shadows make a second scheme, which is superimposed on the first, providing a counterpoint in illumination. Such an interplay of light, complicated still further by various intensities of light from the sides reveals the full richness of sculpture forms and makes complex character of even the most simplified. Furthermore the substitution of vibrating foliage for the hard, finite walls of a great gallery, and of a million blades of grass for its marble floors, greatly assists the transformation of familiar Tate furnitures into figures which live and breathe. [7]

Moore presented two carved stone sculptures, Recumbent Figure 1939 and Three Standing Figures 1947. Of the latter, Moore said he had been trying to express a sense of unity that epitomised wartime Britain:

The background of trees emphasised their outward and upward stare into space… the bringing together of these three figures involved the creation of a unified human mood… I wanted to overlay it with the sense of release, and create figures conscious of being in the open air, they have a lifted gaze, for scanning distances. [8]

While gazing at the skies expresses a hope towards the future is something of a convention, post-WW2 Moore’s sculpture had a more unsettling connotation: scanning for potential catastrophe. The sculpture still stands in Battersea Park today as an alternative kind of monument to those who survived the war, during which they were forever changed.

*

The exhibition’s organisers had anticipated an audience of 30,000 people over the five months, but expectations were quickly surpassed: 24,000 people viewed the exhibition in the first week alone. The total number of visitors tallied in around 150,000 – it was safe to say Strauss’s idea for an ambitious outdoor sculpture exhibition was not so ‘silly’ after all.

The exhibition’s significance as a potential site of social transformation drew official parties of European socialists and trade-unionists, including one Bulgarian legation which was inspired to stage a similar exhibition in Sofia. [9]

After the great success of the 1948 exhibition, the London County Council decided to hold another in 1951 to coincide with the Festival of Britain, a celebration of British industry, arts and science. Organised by Strauss’s successor, Alderman Ruth Dalton, the exhibition ran alongside the merrymaking in the park’s new Festival Gardens. Loans were secured from institutions in France and from MoMA in New York. Among the 44 exhibits were works by Reg Butler, Lynn Chadwick, Frank Dobson, Eric Gill, Alfred F. Hardiman, Barbara Hepworth, Karin Jonzen, Gilbert Ledward, F.E. McWilliam, Bernard Meadows, Henry Moore, John R. Skeaping, Havard Thomas, Charles Wheeler, Jean Arp, Ernst Barlach, Max Bill, Alexander Calder, Jacob Epstein, Alberto Giacometti, Heinz Henghes, Maurice Lambert, Jacques Lipchitz, Aristide Maillol, Marino Marini, Antione Pevsner, Auguste Rodin, Willi Soukop and Karel Vogel. Attendance that year was lower, albeit still impressive, at 110,000.

c Philip Jones Griffiths and Magnum Photos, 1960

Reg Butler, The Bride, 1954–61. Courtesy London Metropolitan Archives

Phillip King, Slant, 1965. In background: Anthony Caro, Month of May, 1963.

L-R: Eduardo Paolozzi, Palm, 1965; Tokio, 1964; Hamlet in a Japanese manner, 1966.

While the following two editions were held in Holland Park, the exhibitions returned to Battersea in 1960 through to 1966. The 1960 show compared works by artists from Britain and France. The 1963 edition also took nationality as a theme, pitting British and American artists against each other. A reviewer for the Times suggested that MoMA had fielded a ‘strong team’ for the show, which ‘sets up something of a challenge both to its well-mannered, English parkland setting, and to the figurative British sculpture arranged to confront it on the main slope of rising ground’.[10] 1963 was notable for its inclusion of Barbara Hepworth: Single Form (Memorial), 1961-62, which still stands by the lake in Battersea Park today.

1966 saw more contemporary, colourful work on display than in any previous exhibition. This led some critics to question the suitability of such works in a landscape-based show. However, the art historian and curator Alan Bowness noted that the open air shows had helped to create a way of looking at, and appreciating, the work of Moore and his generation: ‘the revolutionaries of the 1948 exhibition, Moore and Hepworth, now appear as the old masters of the 1966 one. They alone, with another pioneer, McWilliam, have shown every time. We can appreciate how they have dominated these exhibitions, which have in turn provided the perfect setting for their sculptures. In a way they [the exhibitions] created their aesthetic.’ [11]

The immense popularity and democratic accessibility of the unprecedented exhibition series in some ways led to its eventual demise: numerous other municipal sculpture parks began to spring up across the rest of the UK and Europe, and by the 60s the format was no longer considered unusual or surprising. Even so, it all began in Wandsworth: art historians widely agree that the phenomenon of the sculpture park owes almost everything to the vision and popularity of Strauss’s radical idea to host a world-class exhibition in our very own Battersea Park.

Endnotes:

[1] Strachan, W. J., Open Air Sculpture in Britain, London: Zwemmer/Tate Gallery, 1984, p.9.

[2] LCC/MIN 9021. LCC Press Briefing (August 1948).

[3] Letter to Powe, F. W., 15 May 1946, LMA (LCC/MIN/9017).

[4] Roger Berthoud, The Life of Henry Moore, London: Faber & Faber, 1987, p.210.

[5] Strauss quoted in Coxhead, E., ‘Life in the Parks’, Liverpool Post, 20 May 1948.

[6] Open Air Exhibition of Sculpture, London: LCC, 1948.

[7] Patrick Heron, ‘Sculpture in the Park’, New Statesman (29 May 1948), pp.433-4.

[8] Sculpture in the Open Air: A Talk by Henry Moore on his Sculpture and its Placing in Open-Air Sites, ed. Robert Melville, 1955.

[9] South London Press, 21 September 1948.

[10] ‘American and British Sculpture’, Times, 30 May 1963, p.15.

[11] ‘Introduction by Alan Bowness’, Sculpture in the Open Air, Greater London Council, London, 1966.

Sources:

Burstow, Robert Burstow, ‘Modern Sculpture in the Public Park: A Socialist Experiment in Open-Air ‘Cultured Leisure’, 2006.

Jennifer Powell, ‘Henry Moore and ‘Sculpture in the Open Air’: Exhibitions in London’s Parks’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015.

Melanie Veasey, ‘The Open Air Exhibition of Sculpture at Battersea Park, 1948: A Prelude to Sculpture Parks’, Garden History, Summer 2016, Vol. 44, No. 1, pp. 135-146.