Spotlight: Ecstatic Antibodies Thirty Years On

Wandsworth has long been home to radical artistic practices. Thirty years ago Battersea Arts Centre hosted a groundbreaking art exhibition titled Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology, which offered bold and urgent perspectives on a global health crisis and sparked a new discourse unavailable via mainstream cultural media channels.

To mark its anniversary, University of Roehampton PhD doctoral candidate D Mortimer talks to art historian Dr. Theo Gordon about its legacy and how it provides a model of collective action we can still learn from today.

TG: What does safer sex mean to you?

DM: Condoms and STI tests I guess?

TG: Yeah, but what does that like, mean? How does that live out for you? How are you talking about safe sex in your life and with your partners? In what context are you allowed to talk about safe sex? Does society even allow you to have a discourse of sex and pleasure?

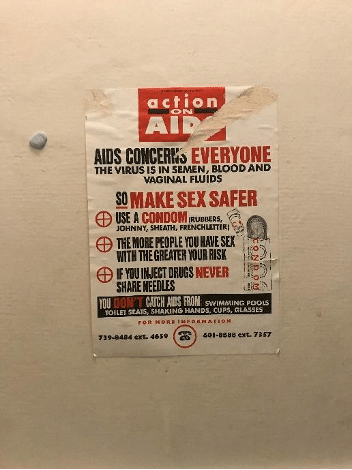

I have a studio above a public library in Stoke Newington. The upper rooms and loos haven’t been refurbished in decades I imagine. Every time I use the loo I stare at a poster on the wall opposite. It has a strip torn off the front but otherwise it has survived the decades remarkably intact. The chunky red and black ink is still vivid. The poster is headed ‘Action on AIDS.’ Each time I use the loo in my studio I am forced to think about safer sex and AIDS. This poster stages an intervention in my daily routine. It is a social media.

Ecstatic Antibodies, an exhibition at Battersea Arts Centre in 1991, was designed to counter the received discourse around AIDS and to provide a social and cultural space for talking about safe sex that wider society, in its puritanism, did not allow for.

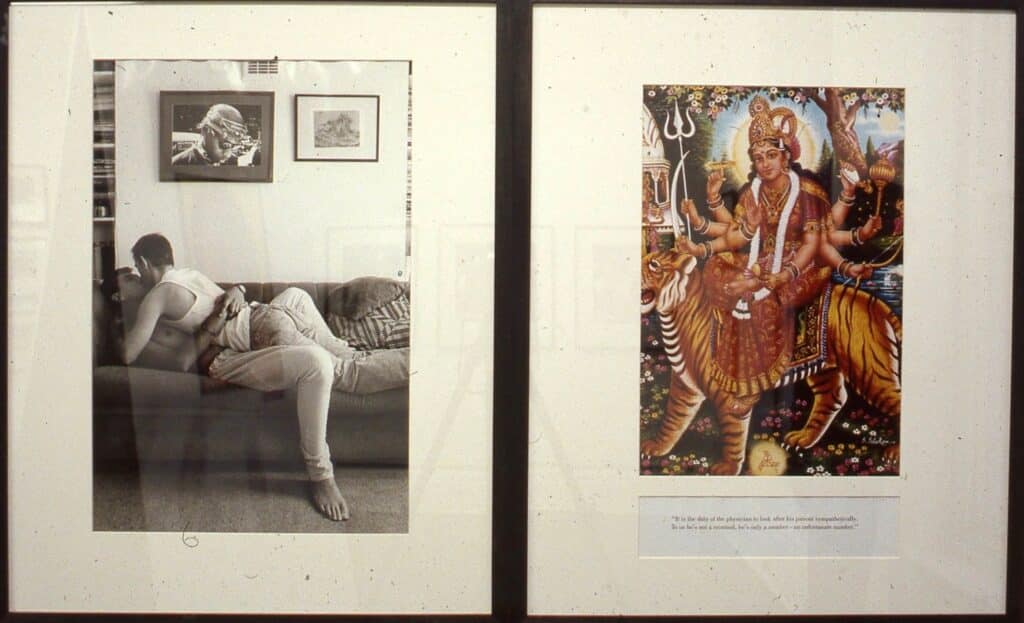

South London photographers Sunil Gupta and Tessa Boffin belonged to The AIDS and Photography Group, who assembled at the London Lesbian and Gay Centre in 1987. It was in this group that Gupta and Boffin, along with a shifting roll call of contributors, would go on to design and organise Ecstatic Antibodies. “This was a huge project that lasted for years. Trying to get money. It was very much a world building enterprise,” Dr. Theodore Gordon tells me. Two exhibitions rose out of those initial meetings: Bodies of Experience (1989) and Ecstatic Antibodies (1990-91). The former took a more straight documentary approach in its response to the epidemic, the latter aimed to radically re-form AIDS discourse in print media.

“There were fewer barriers then,” says Gordon of the time, “but they were different barriers.” Section 28 was passed in the middle of planning Ecstatic Antibodies, a UK law that prevented the promotion of homosexuality by local governments and schools. (Enacted on 24 May 1988, Section 28 of the Local Government Act was repealed in 2000 in Scotland and in 2003 in England and Wales.) I ask Gordon about the exhibition’s history: “The reception to it was quite oppositional. The work is difficult. It was first shown in York in the Impressions Gallery of Photography. And then it was due to be on in Salford but was censored because of Section 28. After that it travelled to Birmingham, Cardiff, Battersea, Glasgow, Montreal, Dublin, Worcester and Wolverhampton.”

“Why was it censored in Salford and nowhere else?” I ask him. “Because some of the work used gay porn, it was asked that the artists put up an ‘Adults only’ notice on one part of the exhibition. Apparently in Salford they didn’t have the space to do that.” In Salford, Section 28 meant there wasn’t the space, literally, to have a conversation about safer sex or gay sex, at all.

Wandsworth, however, welcomed the conversation. The multi-media exhibition opened at Battersea Arts Centre on 23 January 1991 and ran until 24 February that same year. Exhibiting artists included photo duo Rotimi Fani-Kayode and Alex Hirst, film-makers Stuart Marshall and Isaac Julien, painter David Ruffell and artist Joy Gregory. The reception was mixed. Time Out called the exhibition ‘challenging and provocative’ and Paul Burston, writing for City Limits magazine in 1991 said it showed ‘art can be interventionist with a definite social function.’ Elaine Williams’ review in The New Scientist on the other hand betrays a phobia on the subject. She describes how she ‘sensed something distinctly ghetto-like about this show, which is the work of London lesbian and gay artists’ and that, on viewing Nicholas Lowe’s installation (Safe) Sex Explained (1988), she ‘escaped the room with relief.’

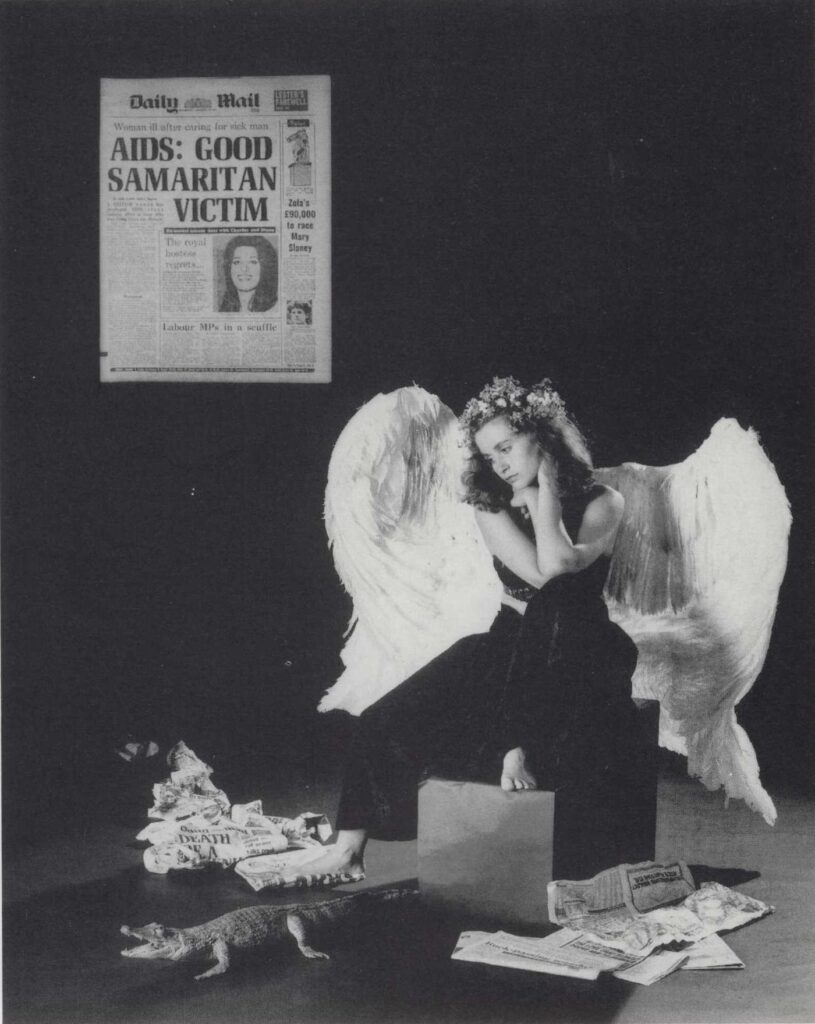

Tessa Boffin’s triptych Angelic Rebels (1989) remains one of the most written about works in the exhibition and was recently reshown as part of Hot Moment at Auto Italia, London in 2020. The work reimagines Albrecht Dürer’s Melancolia I or Angel of Melancholy (1514) in an AIDS climate. Durer’s angel is a femme lesbian, slumped and rifling through the tabloids of the age. Boffin’s photographs problematise the idea that Lesbian sex was clean, safe and ‘pure’. The angel/lesbian learns about safer sex practices and through this education her potential to be an ‘angelic rebel’ is realised. She ascends out of her chair, half dressed in kink gear. Her partner’s grip tethers her. In this grounded flight the message of a supported safer sex is translated.

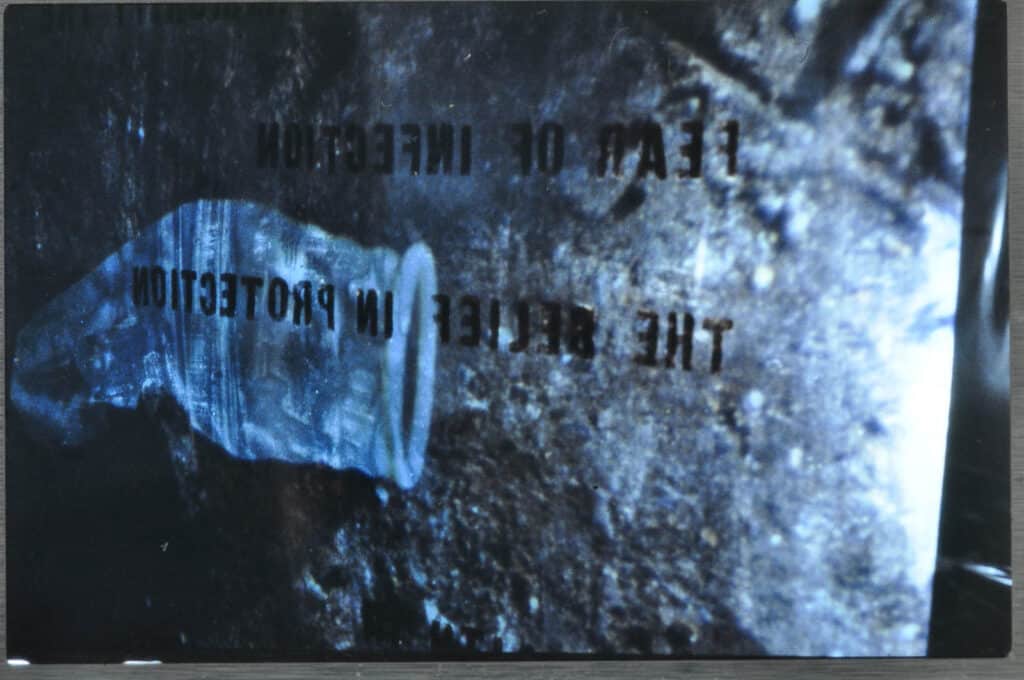

Boffin’s series reflects the exhibition’s main concern, which is the politics of representation. Gordon explains: “a lot of the work in Ecstatic Antibodies comes back to what can be represented and how? The work is also consciously art historical. Durer’s Angel of Melancholy of course, but also the black box setting. The figures exist in another place.” This black space, as well as being a no-place suggestive of social ostracisation, establishes an imaginative space where conversations about sex and pleasure in the context of AIDS can be strategically had through the power of artistic intervention. There was a lively debate in the 1980s on what documentary was or could be, says Gordon. It was fast becoming clear to these artists that “the same tool [photographic representation] which was used against them, could be used as a form of questioning and relating.” In 1986, as part of a public health campaign, a leaflet drop around AIDS was initiated, coinciding with the now infamous “tombstone” advert that configured AIDS as a deadly punishment – this was the prevailing attitude in the media toward gay people with HIV/AIDS.

By the time the exhibition was being organised, national funding for education on AIDS had dried up. “One of the things the exhibition is responding to” Gordon tells me “is this shrinkage of resources.” By 1989, AIDS was disappearing from public discourse, in part due to Section 28. “Think about the imaginary that leaves behind,” he says. The exhibition was designed to highlight nuanced conversations around AIDS from marginalised voices such as black people, lesbians and gay men. The artists wanted to counter the mainstream representation of HIV/AIDS and “the inherent sexism and racism of much media reporting.” The work was consciously pro-sex and pro-queer. “It’s not about abstinence” says Gordon. In these ways the exhibition fills a discourse gone silent with myriad perspectives that not only tell a different story but tell the different story, differently.

David Ruffell’s (1940-1989) Scenarios of Departure series

Many of the contributors – the ones that survived the eighties – suffered the debilitating injuries of grief and trauma. By the early nineties the community was the walking wounded. Arts organising and fundraising in the increasingly market-driven, careerist environment of the 90s ‘art world’ was an immense struggle.

Ecstatic Antibodies signifies a complete reterritorialization of the discourse on AIDS in the UK. The work of remembering is precisely that. Work. Whilst Gupta, Boffin and friends were labouring to produce this exhibition, the media was working just as hard to construct a monolithic, monstrous gay male identity. Ecstatic Antibodies was about self-naming at a time when being a gay man meant one thing.

Cliché, mis-representation and false mythology take collective pressure to resist. It is up to our generation to do the work, not only of remembering but of re-visioning. Novelist and senior lecturer at University of Roehampton Isabel Waidner’s recent article ‘An Alternative Art History of the 1990s’ for Frieze magazine provides an example. Waidner undoes the dominant narrative surrounding the Young British Artists (yBas), a loose group of British artists who began to exhibit together in 1988 and became famous for their shock tactics and entrepreneurial attitude. ‘Arguably,’ Waidner writes, ‘the yBas contributed to the marginalization of a generation of 1980s Black British artists.’ Ecstatic Antibodies, Waidner suggests, was foreclosed not only by Section 28 but by the rise to fame and reactionary tenure of the yBas.

In my work as a writer, thinking alongside a community of other trans writers and artists, I am interested in how we name ourselves against a backdrop of gross institutional misnaming. As well as being an act of self-naming Ecstatic Antibodies was an exercise in collective community organising from artists and photographers that we can learn a lot from today. At a time when London’s queer artist/activist community has been rocked by personal grief and public tragedy, and a skeleton trans healthcare system is contributing to the deaths of working class trans people and queer people of colour, it is vital we actively remember the labour and radical vision that, in the most extreme of circumstances, went into realising this 1991 exhibition.

D Mortimer, July 2021

D Mortimer is a London-based writer whose work focuses on transgender and crip narratives. They are a Techne PhD doctoral candidate at the University of Roehampton, Wandsworth.

Dr. Theodore Gordon is the Terra Foundation For American Art post doctoral fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. His research focuses on print cultures and safer sex.